CHAPTER 2 - Designing and building a ULF camera

Over the years, the majority of my work in photography has been done with 8×10 inch view cameras. Still my favorite format, 8×10 works beautifully but like everything, has its limits. My plan was to move up to an 11×14 inch negative (almost twice the film size and print sharpness of 8×10) in order to make images of landscape subjects as large gelatin silver murals for museums and galleries. Eventually, to move forward I needed a camera to make 11×14 inch negatives so I began to search for one. My research led to two conclusions; used available cameras were either antiques or junk and new ones (still available) were pricey. Neither option worked for me so I began to think about building one. Although I am fairly resourceful aund modestly skilled in wood and metal working, I knew this was out of my league. So, for the next few months I concentrated on designs and features I wanted. I studied other camera designs and made drawings incorporating different camera features I could use. After several months, I knew I had a crude but workable concept for a serious camera.

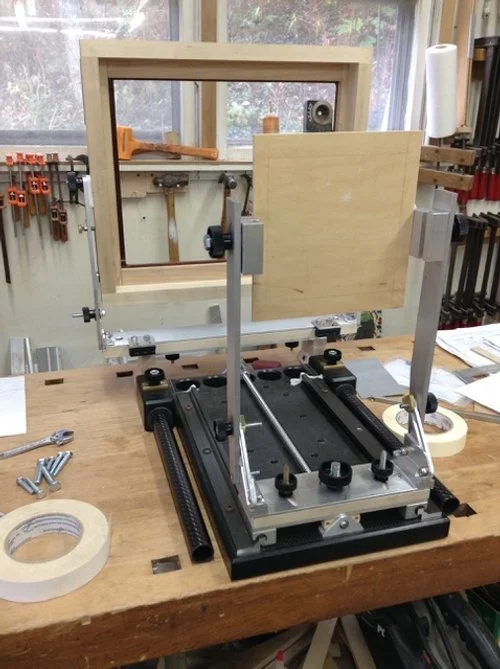

Front standard and locking hardware.

I talked about this project with my friend Robert “B” Goode. Our conversation lit the fire and B offered his services. I knew right away that this was the right move since B is a gifted artist, skilled industrial designer and master wood/metal worker. He has a sophisticated shop and builds museum quality fine art furniture and sculpture. He is a visionary conceptual and abstract mural painter. And he lives nearby. After a few meetings, we began to rework my rough sketches and think about materials. It was clear that our shared vision did not include plywood, plastic or other crude materials. This camera would be made of state of the art elements and weight and function would be top concerns. After considerable research, our materials list came down to carbon fiber, aircraft quality aluminum, brass, stainless steel, high molecular weight polyethylene and american rock maple.

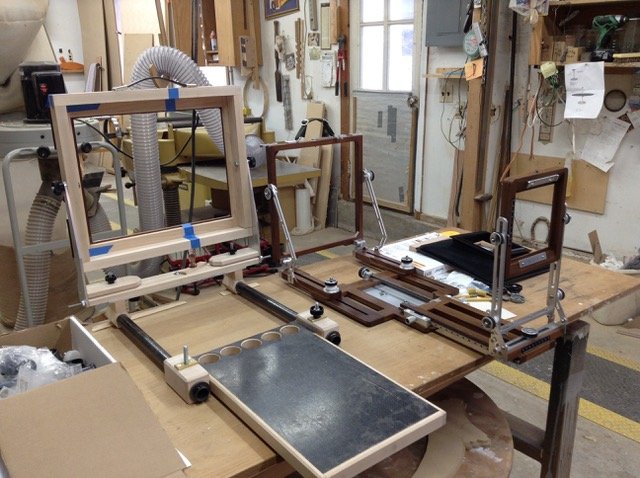

Aluminum hardware completely machined and awaiting anodizing.

My drawing skills are limited, but B was able to quickly take my rough scratchings and verbal descriptions and render them accurately with pencil and paper in perspective. We began to fabricate an entire Ultra Large Format camera piece by piece. The camera base was first. It was made from a 12”×24”×1” thick panel of closed cell structural foam sandwiched between two pieces of carbon fiber veneer. These weightless and unbendable panels, used in the bodies of jet aircraft, made a beautiful super strong base for the camera.The front and rear standards were created next. B and I searched for a strong, light high-tec alternative to rock maple which would have been metal or solid machinable carbon fiber, but at that time carbon fiber was too expensive. So we forged ahead with a few parts made of rock maple - one of the most dimensionally stable woods available and well respected by sculptors and master furniture makers.

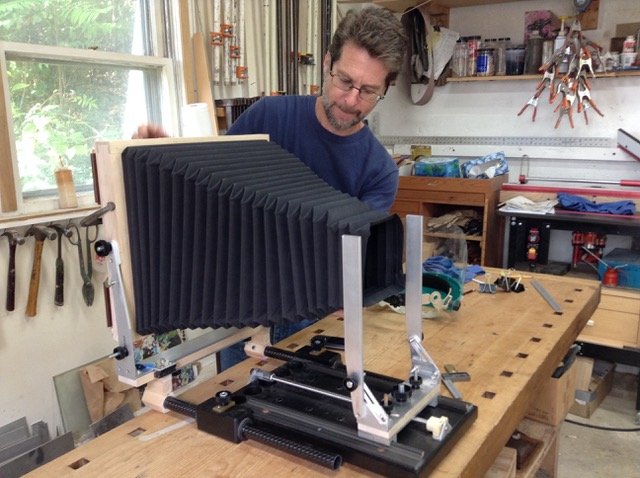

First attempt to fit new bellows to the camera. Front standard almost complete.

I wanted this to be a horizontal camera to save weight and reduce size, so this factored heavily into the design - particularly in how it folds. We moved on to the adjusting and locking mechanisms. View cameras are still unique despite their basic design being well over 150 years old. They have the ability to precisely control focus, perspective and image position by allowing the positioning of the lens and film planes independently. These positioning controls are known as tilt, swing, shift and rise and fall. This 11×14 camera may be one of the most sophisticated units of its kind in this regard. Rear swing and tilt locks are very important to keep the camera back rigid while a film holder is being loaded. ULF film holders are enormous. Inserting one into the camera back can throw rear standard adjustments off ruining a potentially great image and an expensive piece of film. Most rear standard tilts use one set of locks to hold an adjustment. This camera uses three separate sets of locks for the rear tilt alone. Two to hold adjustments and one set to add extra rigidity when carrying the folded camera. We spent countless hours designing hardware, creating mockups with cardboard and fiberboard and testing each part to ensure exact fit and function. Finally, dozens of shiny finished 6061T custom made aluminum parts were shipped off to California for black anodizing. Final assembly of the body without bellows was done more than a year after we started. Next, the bellows had to be designed and manufactured. We worked with Turner Bellows in Rochester New York who guided us in measuring the camera body correctly so that they could custom manufacture bellows that would fit perfectly. They did an amazing job and the bellows (a very difficult thing to make by hand) fit and worked as promised. This camera has about thirty four inches of extension (to accommodate longer lenses) yet can be compressed to about three inches to focus at infinity with extreme wide angle lenses.

B. Goode fitting bellows to front standard. Nearing completion.

Finished camera fully extended.

Our initial goal was to keep the camera body weight low-around 14 pounds.That soon became unattainable for reasons of structural strength. The final total camera body weight is 22 pounds. I carry it on a custom backpack frame with a large Ries wooden tripod in my hand (friends and assistants carry the rest). Twenty-two pounds feels light in comparison to the 40 pounds of 8×10 camera gear I often carry alone. After almost two years in the making, the camera works like a dream and the incredible Ilford FP-4 black and white negatives enlarge to razor sharp beautiful prints up to 42×72 inches. Of so many wonderful, collaborative and creative projects in my life, this one with my friend B. Goode was the finest.